Mr. Robertson's Corner

A blog for students, families, and fellow educators. Meaningful reflections, stories, ideas, advice, resources, and homework help for middle school, high school, and college undergraduate students. We're exploring history, philosophy, critical thinking, the trades, business, careers, entrepreneurship, college majors, financial literacy, the arts, the social sciences, test prep, baseball, the Catholic faith, and a whole lot more. Join the conversation.

Pages

- Home

- About Aaron and this blog

- How to get the most from this blog

- Aaron's teaching philosophy

- Aaron's Resume / CV

- Tutoring services

- Noteworthy interviews by Aaron

- Connect with Aaron

- Aaron - Testimonials

- Career readiness resources

- ACT test strategies

- Writing prompts for fun and practice

- Exploring the world of music

- The importance of reflection

- How to get more out of reading

- Choosing quality sources for research

- Mental health and suicide prevention

- Better study habits

- The many benefits of volunteer work

- The benefits of networking

- Google Chromebook help for students

- Free worksheets and learning games

- Bible studies / Scripture reflections

- Watch The Chosen for free at Angel Studios

- Men of Christ

- Democracy and the 2024 presidential election

Search This Blog

Saturday, April 13, 2024

Missouri Compromise

Introduction

The Missouri Compromise, enacted in 1820, was a pivotal legislative act in the early history of the United States that aimed to balance the power between slave and free states. This compromise, which admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, sought to maintain a delicate balance in Congress. It also established a geographic line (the 36°30' parallel) across the Louisiana Territory, north of which slavery was prohibited (except in Missouri). The Missouri Compromise was one of the first major attempts to address the growing sectional conflict over slavery and set a precedent for future compromises in the antebellum period.

Background: A nation divided

As the United States acquired more territory and admitted new states, the balance of power between North and South became increasingly contentious. The admission of Missouri as a state in 1819 triggered a national debate over the expansion of slavery. The North saw the expansion of slavery as a threat to the concept of equal opportunity and to the balance of power, while the South viewed the restriction of slavery as a threat to its economic interests and political power.

The terms of the compromise

The Missouri Compromise consisted of three main conditions:

Missouri's admission as a slave state: Missouri would be admitted to the Union as a slave state, which appeased Southern interests concerned about maintaining a balance of power in the Senate.

Maine's admission as a free state: To balance Missouri’s admission, Maine was admitted as a free state, which pleased Northern interests.

Prohibition of slavery north of 36°30' parallel: Perhaps the most significant aspect of the compromise was the stipulation that in the rest of the Louisiana Purchase north of latitude 36°30' (the southern boundary of Missouri), slavery would be prohibited. This provision attempted to set a long-term framework for the expansion of new territories.

Impact and legacy

Immediate effects

The Missouri Compromise temporarily resolved the crisis over the admission of new states and the expansion of slavery, but it was a clear sign of the growing sectionalism that would eventually lead to the Civil War. It provided a short-term political solution but did not address the underlying moral and economic tensions that divided the nation.

Long-term consequences

The Missouri Compromise had significant long-term implications for the United States. It established the precedent of Congressional intervention in the expansion of slavery, which would be a contentious issue in future compromises and decisions, such as the Compromise of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The compromise also highlighted the increasingly sectional nature of American politics.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Missouri Compromise was a crucial moment in the history of the United States, representing an early attempt to deal with the divisive issue of slavery as the nation expanded. While it succeeded in temporarily maintaining the balance of power between slave and free states, it also highlighted the profound divisions within the country. The compromise was a testament to the complexities of managing a nation with deeply entrenched economic, moral, and social differences. Its legacy is a reminder of the challenges that the United States faced in its early years and foreshadowed the greater conflicts that would eventually lead to the Civil War.

Kansas-Nebraska Act

Introduction

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 was one of the most consequential pieces of legislation in American history. Proposed by U.S. Senator Stephen A. Douglas, a Democrat representing Illinois, the Act created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, opening new lands to settlement and, most controversially, allowing the settlers there to decide for themselves whether to allow slavery through the principle of popular sovereignty. This legislation overturned the Missouri Compromise, which had prohibited slavery in that region for over three decades, and it significantly escalated the sectional conflict that would eventually lead to the American Civil War.

Background: The desire for a transcontinental railroad

The origins of the Kansas-Nebraska Act are closely linked to the development of a transcontinental railroad. Senator Douglas envisioned Chicago as the eastern end point of the railroad, which required organizing the region west of Missouri and Iowa into U.S. territories. However, this region lay north of the latitude 36°30' line established by the Missouri Compromise as the boundary between free and slave territories.

The provisions of the Act

To gain Southern support for the Act and the railroad, Douglas proposed applying the principle of popular sovereignty to the new territories, allowing settlers to vote on the legality of slavery. This was a direct contradiction to the Missouri Compromise, which had prohibited slavery in the same latitude. The Act was passed in May 1854 and signed into law by President Franklin Pierce, a Democrat, leading to immediate and significant repercussions.

The impact of the Kansas-Nebraska Act

Political realignments

The Act led to a profound realignment of American politics. The Whig Party, already weakened, disintegrated under the strain of the slavery issue, while the Democratic Party became increasingly sectionalized. The political turmoil catalyzed the formation of the Republican Party, which unified various anti-slavery groups and individuals committed to opposing the spread of slavery into the new territories.

"Bleeding Kansas"

The most immediate and violent impact of the Act was in Kansas Territory, where pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers rushed to establish a majority. The resulting conflict, known as "Bleeding Kansas," was marked by widespread violence and fraud in electoral processes. This mini civil war served as a grim preview of the national conflict that would erupt less than a decade later.

National divisions

The Act exacerbated sectional tensions to a breaking point, with Northerners outraged over the repeal of the Missouri Compromise and Southerners emboldened by the opportunity to expand slavery into new territories. The debate over the Act and its implementation revealed the deep moral, economic, and political divisions between the North and South.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 was a pivotal moment in the lead-up to the American Civil War. By introducing popular sovereignty into the territories, the Act not only nullified the Missouri Compromise but also transformed the political landscape of the United States. The violent conflicts in Kansas and the national uproar that followed demonstrated the intractability of the slavery issue and signaled the failure of legislative compromise as a means to resolve the sectional strife. The Act not only shaped the course of American history by accelerating the approach of war but also underscored the profound consequences of political decisions on the fabric of the nation.

Wilmot Proviso

Introduction

The Wilmot Proviso was a proposed amendment to a military appropriations bill in 1846, introduced by Pennsylvania Congressman David Wilmot. Its purpose was simple yet profoundly impactful: to ban slavery in any territory acquired from Mexico as a result of the Mexican-American War. Though never enacted into law, the Wilmot Proviso ignited a fierce debate over slavery in the United States, exacerbating sectional tensions between the North and South and foreshadowing the conflicts that would eventually lead to the Civil War.

The context of the Wilmot Proviso

The Mexican-American War (1846-1848) resulted in vast territories falling into American hands, raising immediate questions about the status of slavery in these new lands. The issue of whether these territories would be slave or free heightened tensions in an already polarized nation. David Wilmot, a Northern Democrat, introduced his proviso as a reaction to President James K. Polk’s (who was also a Democrat) administration, which many Northerners believed was dominantly pro-Southern and pro-slavery.

The provisions of the Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso stipulated that, "as an express and fundamental condition to the acquisition of any territory from the Republic of Mexico by the United States, neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any part of said territory." This straightforward legislative language aimed to ensure that the expansion of the United States would not lead to the expansion of slavery.

The political and social impact

Immediate reaction

The proposal sparked immediate controversy. It passed the United States House of Representatives multiple times, where Northern states held a majority, but it consistently failed in the Senate, where the balance was more even between free and slave states. The Proviso thus highlighted the growing power struggle between North and South over the future of slavery in America.

Long-term consequences

Although it never became law, the Wilmot Proviso had significant long-term effects on American politics. It contributed to the realignment of political parties: many Northern Democrats and Whigs who supported the Proviso became disillusioned with their parties’ handling of the slavery issue, eventually forming the Republican Party in the 1850s with a platform that opposed the extension of slavery into new territories.

The Proviso also inflamed sectional divisions, making it a precursor to later legislative conflicts over slavery. The debates it sparked helped set the stage for the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and ultimately the secession of the Southern states.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Wilmot Proviso was a critical moment in the antebellum period of American history. It not only highlighted the pressing issue of slavery in new territories but also underscored the deep divisions within the country. By bringing the issue of slavery to the forefront of national discourse, it played a crucial role in the political realignment that preceded the Civil War. The Wilmot Proviso remains a testament to the complexities of American expansion and the moral and political challenges of a nation on the brink of division. The unresolved tensions it revealed between freedom and slavery encapsulate the struggle for the soul of the burgeoning American republic.

The Compromise of 1850

Introduction

The Compromise of 1850 stands as a crucial juncture in the history of the United States, marking a temporary détente in the bitter regional conflicts over slavery that threatened to tear the nation apart. This complex set of laws passed by Congress aimed to address the territorial and slavery controversies arising from the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) and the subsequent acquisition of new lands. The Compromise had far-reaching impacts on the North, the South, and the emerging territories, setting the stage for the intensifying national debate over slavery that would eventually culminate in the Civil War.

Background: The acquisition of new territories

The end of the Mexican-American War saw the U.S. gain vast territories in the West, including present-day California, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico. This acquisition posed a significant question: Would these new territories permit slavery? The issue was incendiary, with Southern states advocating for the extension of slavery into new territories and Northern states resisting.

Key provisions of the Compromise

The Compromise of 1850 consisted of five key bills passed in Congress, which together sought to balance the interests of the slaveholding South and the free North:

California's admission as a free state: California's entry into the Union as a free state tilted the balance in the Senate towards the free states, a significant point of contention for the South.

Fugitive Slave Act: Arguably the most controversial aspect of the Compromise, this act mandated that escaped slaves found in free states be returned to their owners in the South. This law was bitterly opposed in the North and led to increased support for abolitionist movements.

Abolition of the slave trade in Washington, D.C.: While this measure banned the trade of slaves in the nation's capitol, it did not outlaw slavery itself there, representing a symbolic gesture towards anti-slavery forces.

Territorial status for Utah and New Mexico: This provision allowed the residents of these territories to decide the issue of slavery by popular sovereignty when they applied for statehood, effectively sidestepping the issue at the federal level.

Texas-New Mexico boundary and debt relief: Texas was compensated financially for relinquishing claims to lands that were part of New Mexico territory, which helped resolve longstanding disputes and reduced tensions.

Impact and analysis

The Compromise of 1850 achieved its immediate goal of keeping the Union together, but it was not without its costs, particularly in terms of the intensification of sectional animosities. The Fugitive Slave Act, in particular, had a profound impact on the North, galvanizing public opinion against the South and its institutions of slavery. The act led to numerous instances of civil disobedience and violent resistance, which made enforcement difficult and sometimes impossible.

Moreover, the principle of popular sovereignty in the Utah and New Mexico territories set a precedent that would later be disastrously attempted in Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, leading directly to the violent confrontations of "Bleeding Kansas."

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Compromise of 1850 was a critical, albeit temporary, solution to the ongoing crisis over slavery in the United States. While it succeeded in postponing the inevitable conflict, it also exposed and deepened the divisions within the country. The Compromise reflects the complexities of managing a diverse and expanding nation and serves as a poignant reminder of the challenges inherent in balancing regional interests and ideologies in a federal union. Ultimately, the Compromise of 1850 delayed but could not prevent the slide towards civil war, highlighting the limitations of political solutions in the face of deep-seated social and ethical conflicts.

Thursday, April 11, 2024

Peloponnesian War Thucydides

Thucydides' account of the Peloponnesian War: A timeless lens into international relations (IR)

Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War stands as a cornerstone in the study of international relations, not only for its historical significance but also for its profound insights into the complexities of human conflict and power dynamics. Written over two millennia ago, Thucydides' masterpiece continues to captivate scholars and readers alike, offering enduring lessons that remain relevant in today's turbulent world.

|

| Thucydides |

Thucydides' work is revered in the field of international relations (IR) for several reasons. Firstly, his emphasis on the role of power and self-interest as primary drivers of state behavior anticipates the realist school of thought in international relations theory. Thucydides famously asserts that "the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must," encapsulating the brutal realities of power politics and interstate competition.

Secondly, Thucydides' meticulous attention to detail and objective analysis set a standard for historical inquiry that remains influential today. His reliance on eyewitness accounts and firsthand sources, combined with his critical assessment of different perspectives, demonstrates a commitment to truth-seeking and intellectual rigor that resonates with modern historians and scholars.

Moreover, Thucydides' exploration of the psychology of conflict and the dynamics of fear, honor, and self-interest among states and individuals offers profound insights into the complexities of human nature and decision-making in times of crisis. His portrayal of the destructive consequences of unchecked ambition, hubris, and the breakdown of moral constraints serves as a cautionary tale for leaders and policymakers across the ages.

In today's interconnected and volatile world, Thucydides' insights into the causes and consequences of interstate conflict remain as relevant as ever. His emphasis on the centrality of power dynamics, the rational calculation of interests, and the perils of unchecked aggression provides a sobering lens through which to analyze contemporary geopolitical rivalries and security dilemmas.

Furthermore, Thucydides' warnings about the dangers of overreach, arrogance, and the erosion of diplomatic norms offer valuable lessons for policymakers grappling with the complexities of modern warfare, terrorism, and nuclear proliferation. His admonition that "the secret of happiness is freedom, and the secret of freedom, courage" underscores the enduring importance of moral courage, prudence, and ethical leadership in navigating the treacherous waters of international politics.

In conclusion, Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War stands as a timeless masterpiece that continues to inform and inspire scholars, policymakers, and students of international relations. By probing the depths of human nature, power dynamics, and the complexities of conflict, Thucydides offers invaluable lessons that transcend the boundaries of time and space. As we confront the challenges of the 21st century, his insights remind us of the enduring truths and timeless wisdom contained within the pages of his ancient text.

Monday, April 8, 2024

Whig Party

Part of an ongoing, occasional series looking at the state of democracy and the political process in the United States in light of the 2024 presidential election.

A brief essay on the Whig Party in the United States. How and when did the Whig Party form? What was the Whig Party's core beliefs and policy agenda? Who were the Whig presidents, and what were their noteworthy accomplishments, if any, while in office? Was the Whig Party in the United States considered a third party?

The rise and fall of the Whig Party in the United States

The Whig Party, a significant political force in the United States during the 19th century, emerged as a response to the shifting dynamics of American politics. Formed in the early 1830s, the Whigs represented a diverse coalition of interests united by their opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic Party. Despite their relatively short existence, the Whigs played a crucial role in shaping American political discourse, advocating for economic modernization, infrastructure development, and a more active role for the federal government.

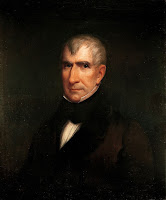

| ||

| William Henry Harrison |

At its core, the Whig Party espoused several key beliefs and policy agendas. One of its primary objectives was promoting economic development through the implementation of protective tariffs, internal improvements such as roads and canals, and support for a national banking system. Whigs believed that these measures would stimulate economic growth and facilitate the expansion of commerce and industry. Additionally, the party advocated for a strong federal government capable of fostering national unity and promoting the common good, in contrast to Jacksonian Democrats' emphasis on states' rights and limited government intervention.

Throughout its existence, the Whig Party produced four presidents: William Henry Harrison (1841), John Tyler (1841-1845), Zachary Taylor (1849-1850), and Millard Fillmore (1850-1853). Of these four, only Harrison and Taylor were elected, while Tyler and Fillmore, their respective vice presidents, assumed the office upon their deaths.

William Henry Harrison, a general and war hero elected in 1840, served the shortest term of any U.S. president, succumbing to pneumonia just a month after his inauguration. Despite his brief tenure, Harrison's election marked a significant victory for the Whig Party, as he ran on a platform emphasizing economic policies favoring industrial development and infrastructure improvements.

|

| Zachary Taylor |

Zachary Taylor, another celebrated general and war hero, assumed the presidency in 1849. Although Taylor's presidency was cut short by his death in 1850, his administration was marked by efforts to address the divisive issue of slavery in the newly acquired territories from Mexico. Taylor's proposed admission of California as a free state sparked intense debate and ultimately contributed to the Compromise of 1850, a temporary resolution to the ongoing sectional tensions between the North and South.

Millard Fillmore, who succeeded Taylor upon his death, continued the Whig Party's emphasis on economic development and infrastructure projects. Fillmore's presidency was overshadowed by the escalating tensions over slavery, particularly with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act as part of the Compromise of 1850. Despite his efforts to maintain national unity, Fillmore's support for the compromise further alienated anti-slavery Whigs in the North and contributed to the party's decline.

The Whig Party's demise can be attributed to several factors, including internal divisions over slavery, the emergence of the anti-slavery Republican Party, and changing socio-economic dynamics in the United States. By the mid-1850s, the party had fragmented beyond repair, paving the way for the Republican Party's ascendance as the dominant political force opposed to the expansion of slavery.

In conclusion, the Whig Party's formation in the early 1830s marked a significant chapter in American political history. Despite its relatively short existence, the Whigs advocated for policies aimed at promoting economic development, infrastructure improvements, and a strong federal government. While the party produced several presidents, including William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, Zachary Taylor, and Millard Fillmore, internal divisions over slavery and changing political dynamics ultimately led to its demise by the mid-1850s. Nevertheless, the Whig Party's legacy continues to resonate in American politics, serving as a reminder of the complexities and tensions inherent in the country's democratic experiment.

The Whigs were not a third party, but a major party during its time

The Whig Party in the United States was not considered a third party in the traditional sense. Instead, it was one of the two major political parties during the mid-19th century, alongside the Democratic Party. As previously noted, the Whigs emerged as a significant political force in the early 1830s in response to the policies of President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic Party. They represented a diverse coalition of interests, including former National Republicans, Anti-Masons, and disaffected Democrats, united by their opposition to Jacksonian policies such as the dismantling of the national bank.

Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, the Whig Party competed directly with the Democratic Party in national elections, fielding candidates for the presidency, Congress, and state offices. The Whigs enjoyed varying degrees of success during this period, electing several presidents, including William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, and Millard Fillmore.

While the Whig Party ultimately declined and disbanded in the 1850s due to internal divisions over issues such as slavery, it was not considered a third party during its existence. Instead, it was one of the dominant political parties of its time, representing a significant portion of the American electorate and competing on equal footing with the Democrats. The rise of the Republican Party in the 1850s, which absorbed many former Whigs and emerged as the primary opposition to the Democrats, marked the end of the Whig Party's prominence in American politics.

Saturday, April 6, 2024

Third party candidates for president

Part of an ongoing, occasional series looking at the state of democracy and the political process in the United States in light of the 2024 presidential election.

In light of the 2024 independent bid of Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. for president of the United States, we take a look at a sampling of other noteworthy independent and third-party presidential campaigns in modern U.S. history. How did these candidates fare? What were their impacts on the elections they ran in?

The impact of independent and third-party presidential campaigns in modern U.S. history

Throughout the annals of American political history, independent and third-party presidential campaigns have emerged as formidable disruptors, challenging the dominance of the two major parties and injecting fresh ideas into the political discourse. While many of these candidates have faced significant hurdles in their quests for the presidency, their campaigns have often left enduring legacies, reshaping the political landscape and influencing the trajectory of future elections. In this post, we will examine some of these noteworthy campaigns and their impacts on the elections they ran in.

1. Theodore Roosevelt (Progressive Party) - 1912:

Perhaps one of the most famous third-party candidates, Theodore Roosevelt, a former Republican president, launched the Progressive Party (also known as the Bull Moose Party) in 1912 after failing to secure the Republican nomination. Running on a platform of progressive reforms, including labor protections, women's suffrage, and conservation, Roosevelt garnered an impressive 27.4% of the popular vote and won six states for a total of 88 electoral votes. While he ultimately lost to Woodrow Wilson, his candidacy split the Republican vote, paving the way for Wilson's victory and highlighting the growing influence of progressive ideals in American politics.

2. George Wallace (American Independent Party) - 1968:

George C. Wallace, the former, as well as future, Democratic governor of Alabama, ran for president in the 1968 election as the candidate of the American Independent Party. Wallace's campaign centered on a platform of segregationist and law-and-order policies, appealing primarily to white voters disaffected by the civil rights movement and social unrest of the 1960s.

In the end, Wallace captured a significant portion of the popular vote, winning 13.5%, along with five states in the Deep South for a total of 46 electoral votes. Wallace's campaign had a profound impact on the election that year. By tapping into racial anxieties among white voters in the South and parts of the Midwest, Wallace effectively split the Democratic vote in many states, contributing to the election of Republican candidate Richard Nixon, the former vice president under Dwight Eisenhower (1953-1961).

3. Ross Perot - 1992 (Independent) and 1996 (Reform Party):

Business magnate Ross Perot's bids for the presidency in 1992 and 1996 shook up the political establishment with his focus on fiscal responsibility and opposition to free trade agreements like NAFTA. Despite lacking major party affiliation, Perot captured 18.9% of the popular vote in 1992 and 8.4% in 1996. While he did not win any electoral votes in either election, he managed to take several counties across the country and even placed second in two states in his 1992 campaign against Democratic candidate Bill Clinton and Republican incumbent George H.W. Bush. It's widely assumed he most likely would have secured an even greater percentage of the popular vote in 1992 had he not dropped out of the race for several months. In any case, both of Perot's campaigns forced the major parties to address issues such as the federal deficit and government spending, leaving a lasting impact on the national conversation surrounding economic policy.

4. Ralph Nader (Green Party) - 2000:

5. Jill Stein (Green Party) - 2012 and 2016:

Physician and activist Jill Stein ran as the Green Party candidate in both the 2012 and 2016 presidential elections, advocating for progressive policies such as Medicare for All, a Green New Deal, and student debt forgiveness. While her share of the popular vote was relatively small (0.36% in 2012 and 1.07% in 2016), Stein's campaigns attracted attention to issues often overlooked by the major parties, such as environmental justice and corporate influence in politics. Stein is running again in 2024.

6. Gary Johnson (Libertarian Party) - 2012 and 2016:

On a side note, Johnson ran for president as the Libertarian Party's candidate four years earlier, in 2012, as well. He originally sought the Republican nomination for the 2012 election before joining the LP. While he only secured 1% of the popular vote, which amounted to some 1.3 million ballots cast for him nationally, his total represents more votes for him than all other third-party candidates combined that year.

Conclusion

In conclusion, independent and third-party presidential campaigns have played a significant role in shaping American politics, often serving as catalysts for change and challenging the dominance of the two major parties. While many of these candidates have struggled to achieve electoral success, their campaigns have nevertheless left indelible marks on the political landscape, influencing policy debates and electoral outcomes for years to come. As Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.'s 2024 independent bid for the presidency demonstrates, the tradition of independent and third-party activism remains alive and well in American politics, offering voters alternative visions for the future of the country.